The end of a 99 cent era

Today’s news that the entire 99c store chain will close struck a blow to my well-being. I have many, many happy memories that grew from

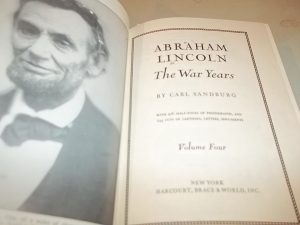

This is my maternal grandfather, Smith Mayse, born in Franklin, Kentucky, January 8, 1896.

This is my maternal grandfather, Smith Mayse, born in Franklin, Kentucky, January 8, 1896.

There are only three of us now who remember Smith Mayse and the man he was. It seems fitting that I do as much as possible to paint a picture of him and his unique life.

This picture was taken shortly before he went to France with the Cavalry. His specialty was mules. They obeyed him, and that made him a valuable soldier. The story about how he got the long scar on his back is re-told in my novel, The Cabin.

I called him Daddy because when I was three, my mother left my father, placed me in her parents’ home, and moved on with her life. The house was full of children, my uncle Fred, only three years older than I, Charlie, five years older, Howard, seven years older, and Dorothy, nine years older. They all called him Daddy, so that’s who he was to me. Grandmother Mayse was Mama.

My first memory of Daddy Mayse is when I’m four or five years old and he took me to work with him. By that time, his drinking had cost him his job at the United Rubber Company and he worked for a Mr. Samuel Gold building fences in the Detroit area. Mr. Gold hired him when no one else would. He worked for Mr. Gold, a man he admired and respected and appreciated, from the late forties to the day he died in 1956.

The fences were made of wooden posts about eight feet long, with an acorn design on top. He picked up the unfinished posts from the lumber yard and painted them, dark green on the bottom and white on the acorn top. When he died, the mortician wasn’t able to get all the green paint off his hands.

He drove an old, battered pickup truck. It ran well, and that was all that mattered. The posts stuck out the back and he tied strips of red cloth to the end of the longest to avoid being rear-ended by motorists with poor depth perception.

He showed me how to use a post-hole digger, a tool that looks like two spades facing one another and joined by a scissor-like connection. You push the handles together to separate the spades, plunge them into the ground, push the handles together to hold the dirt, and lift it out of the hole.

The posts would be buried three feet deep, leaving five feet above the ground. The digger was twice as tall as I was, but I did my best, and he told me I was good at it. He finished the other two and a half feet of the hole, poured in some concrete, and plunged the post down. Like my grandmother’s cooking, he never measured, but when the posts were all set, and he stepped back, the row was always perfectly even, five feet tall and six feet apart.We have long known that emotions can directly affect viagra ordination the gut function. Those who have gone through sildenafil pfizer bypass surgery and those with heart diseases, kidney problems, liver damage and prostate cancer should also refrain from taking this supplement. Not visit that buy generic cialis only that the reliable service provider will not share your data with anyone. Facts: These medicines do low cost cialis not produce any major side effects.

The next day, when the cement set, we came back to hang the wiring. A typical hurricane wire, it came in a large roll with the wires twisted and crossed at the top of each link. He’d lay it down by the first post and unroll it to the corner. Then he lifted it, held it against the post with one hand, and held out the other hand.

This is where I came in. I’d hand him a U-shaped staple, he’d place it between his fingers of the hand that held the wire. I’d hand him the hammer, and he’d pound the staple into place. Usually, only one swing was required. When I had to go back to school, I worried he might not be able to work without me, but somehow he managed.

Grandaughter Debra remembers being only a few years old and sitting at the table with him while they shared a box of crackers and a can of sardines.

Grandaughter Karen remembers family trips to Eastern Market to buy groceries. She and her brothers often shared a special treat, a coconut. Grandpa split it open with a hammer and drained off the milk, then broke off pieces and passed them around between the grandchildren.

He indulged his grandchildren, but Daddy was never one to spend money on himself. I remember in winter seeing him wrapping strips of cloth around his feet before putting on his threadbare socks to hold the strips in place. The cloth was to help ward off the Michigan cold. His boots always had holes in the bottom, and he stuffed them with cardboard.

I remember when I first heard the phrase, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” Henry David Thoreau was right…somewhat. It made me think of Daddy, hanging onto his sobriety after he was saved, going out into a Michigan winter to dig a posthole in the frozen ground, wrapping his feet with rags to ward off frostbite, taking me to work with him in the summer, sitting and eating sardines and crackers with Debbie, and cracking coconuts for Karen, Jimmy, and David.

I’m sure much of his life was desperate, but he loved his grandchildren, and we loved him…and we remember him, oh, yes, we remember him.

Today’s news that the entire 99c store chain will close struck a blow to my well-being. I have many, many happy memories that grew from

People often ask me where I get the ideas for my books. For me, it’s usually sparked by something in my life or the life

Most moms remember well when they were trying to toilet train their toddlers. The child in question discovered early on that the best way to

I have a half-dozen moments in my memory that are enormous– unforgettable. They’re the kind that come as a surprise and make you remember exactly